Rivers in the Serengeti

The Serengeti plains are at an elevation between 1,600 and 1,800 meter above sea level. Several river catchments drain the area. The Mara River in the north flows from the Mau forests in the Kenyan highlands, southwards through the Masai Mara National Reserve, then west through northern Serengeti, out through the great Masarua marshes, and ultimately into Lake Victoria at Musoma. This is the only permanently flowing river in the Serengeti ecosystem. It supports dense riverine forests on its banks in the Mara, and along its major tributaries in Serengeti National Park. South of the Mara are the parallel catchments of the Grumeti and Mbalaget Rivers that form the Western Corridor of Serengeti National Park. Further south there are the much smaller Duma, Simiyu and Semu rivers flowing through Maswa Game Reserve. The area is undulating and dissected by many small seasonal streams that drain into the main rivers.

Hills & mountains

There are bands of hills that rise steeply from this relatively flat landscape. One band forms the north-eastern boundary of Serengeti National Park in the woodlands, running north from Grumechen to Kuko, then joining the Loita Hills in Kenya. The Gol Mountains rise from the Serengeti plains east of the park. Another band stretches from Seronera west along the corridor to form the Central Ranges, and a third group of hills lies in the south forming the Nyaraboro-Itonjo plateau.

Soils & volcanic history

West of the line Mugumu - Seronera the underlying rocks are ancient (600 million to 2.5 billion years) and comprises Precambrian volcanic rocks, banded ironstones and mineral-poor granites. Late Precambrian sedimentary rocks cover this shield and form the central and southern hills. East of Seronera, granite and quartzite form the eastern hills and kopjes. The western corridor is of more recent geological history; it is a complex of unconsolidated sediments and alluvial formations, which form the base for more nutrient-rich soils. The Crater Highlands are volcanoes of the Pleistocene age and comprise basic igneous rocks and basalt. One volcano, Ol Doinyo Lengai, is still active with the last eruption dating back to 2013.

Africa is an old continent. Evidence suggests it is as old as 4 billion years, older than Europe or North America. We can see this old age from the air (so have a good peek when arriving into Kilimanjaro Airport). Millions of years of weathering have flattened mountains and turned much of Africa into a series of endless, rolling plains and hills. One exception is the geologically active East African Rift system.

The East African Rift is the area where two tectonic plates are moving away from one another. The resulting cracks have produced both the immense Rift Valley and the volcanoes on either side of it. Kilimanjaro, Mount Kenya, and Mount Meru are a few of the best-known examples of the Rift's volcanoes. Although Ngorongoro Crater looks like an extinct volcano, geological surveys suggest it never exploded, however most of its immediate neighbours did. Ngorongoro Crater is a caldera, which means the mountain is collapsing on itself as the tectonic plates separate.

The volcanoes of the East African Rift are relatively young. As these volcanoes erupted, they covered the eastern parts of Serengeti with ash and larger particles. This volcanic ash on the plains creates a very specific type of soil rich in minerals. Eastern plains soils contain different salts, such as sodium, potassium, , and calcium. The soil here is shallow because of the formation of a calcareous hardpan, also known as caliche. During the regional rains, salts are washed down into the soil. As water is removed by plant uptake, the soluble substances precipitate and the caliche layer develops and cements through lime. Soils in the Serengeti become deeper (where the hardpan disappears) towards the northwest plains and into the woodlands, because of more rainfall and less calcium. At levels of precipitation too high for hardpan formation, a characteristic soil catena is found. This is the gradient of soil types from ridge top to drainage pump, characterized by a sandy, shallow, well-drained soil at the top transforming to poorly drained and deep silty soil at the bottom. These catenas form because of the long-term downwash of the finer soil particles downslope with surface run-off.

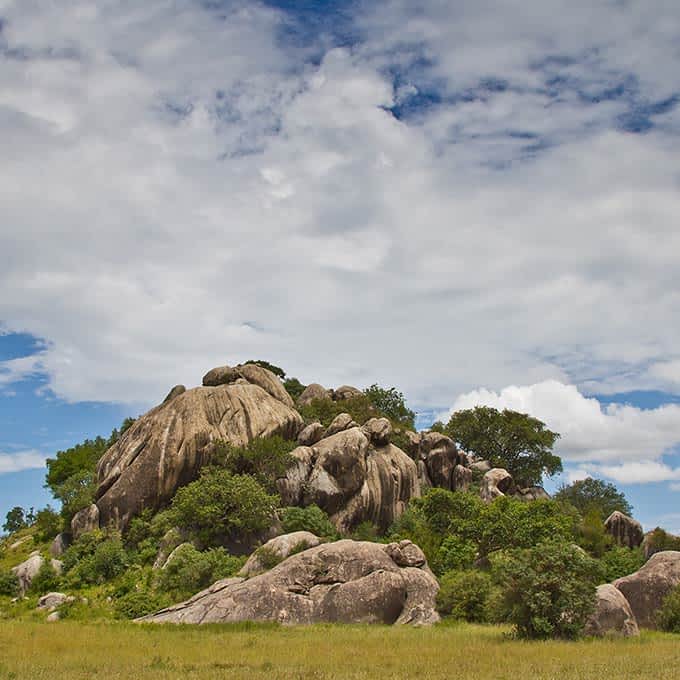

Kopjes

Below the layers of volcanic rock and ash, that form the soil of Serengeti National Park, is a thick layer of extremely old rock. A giant bubble of liquid granite forced its way up from the molten rock below the Earth’s crust and into the Tanganyika Shield in the late Precambrian period. Today, as the softer rocks wear off, it exposes the jagged top of this granite layer, forming kopjes (pronounced ‘kop-eez'). The granite is cracked by the repeated heating and cooling under the African sun and weathered into interesting shapes by the wind. Most kopjes are round or have round boulders on them.

Kopjes are a distinctive feature of the Serengeti landscape and are often referred to as ‘islands in a sea of grass’. They provide protection from bushfires, hold more water in the direct vicinity, offer a hiding place for animals, and a vantage point for predators. Hundreds of plant species grow on kopjes, but not in the surrounding grasslands. Many animal species live on kopjes only because of the presence of these plants, and for reasons of protection. These animals include insects, lizards, and snakes, but also mammals such as shrews and mice, up to large specialist mammals, such as lions. Kopjes are one of the best places to see lions, and occasionally cheetah or leopard.

Further reading